Does the Philippine war on drugs, which comes with an epidemic of streetside extrajudicial killings, make Filipinos feel safe?

For the first time in more than three decades, agents of law enforcement in the Philippines have the freedom to spill blood with impunity because of encouragement from the topmost levels of government . This post is an excerpt of an extensive examination, penned by Lorela U. Sandoval, of this new era of sanctioned blood from all angles. Catch the full story in the first issue of the newly revamped SecurityMatters Magazine, which will hit newsstands and bookstores in early 2017.

——-

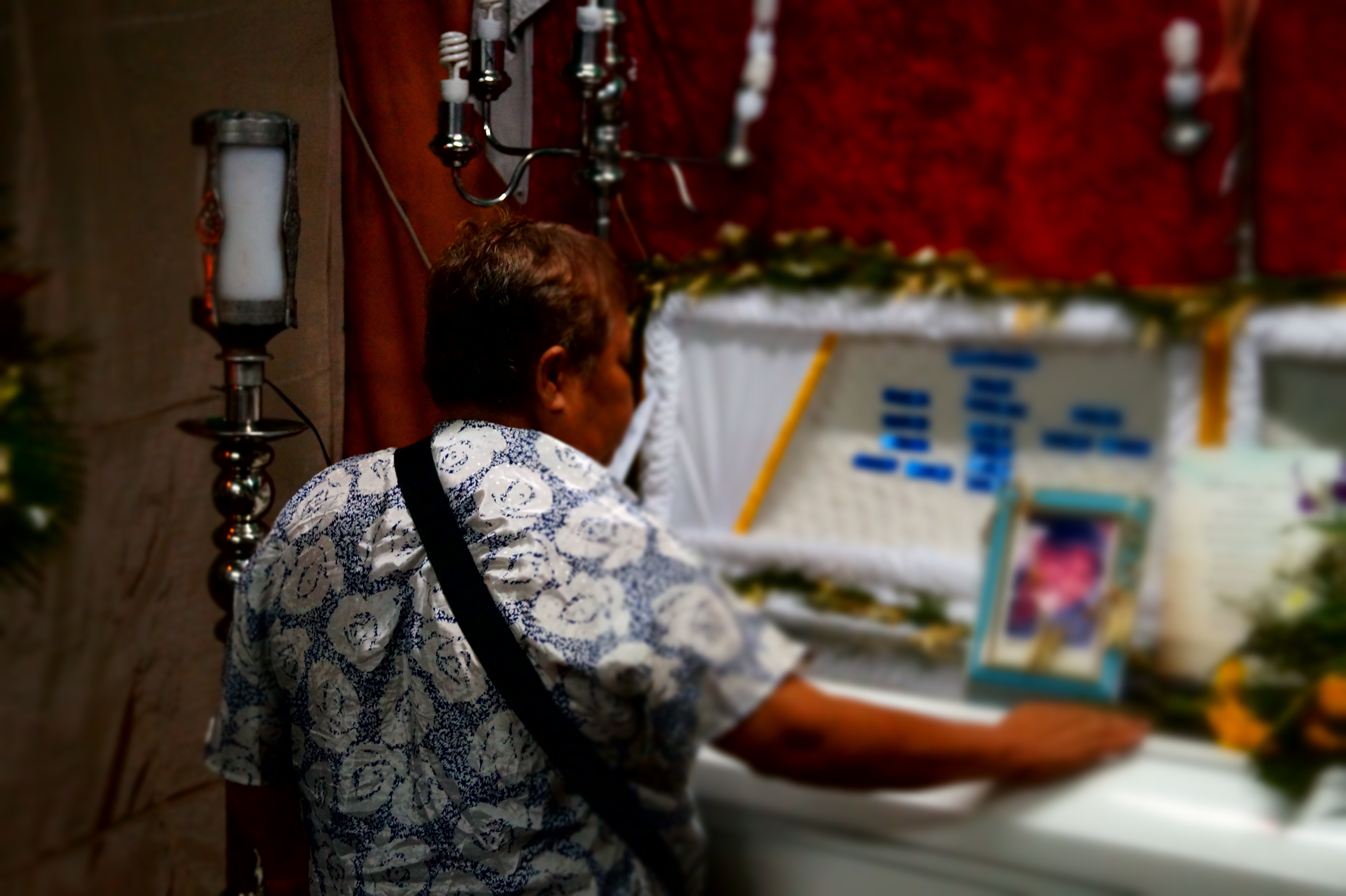

We arrived in a crowded compound in Tondo a little before dark on a Saturday. One side of it was the sound of life and bliss with children at play. The other side was its utmost contradiction: the smell of death and grief amid the wake of a man now possibly among the thousands of casualties of the anti-drug campaign by President Rodrigo Duterte.

We sat facing the casket of *Jay, an alleged pusher found lifeless on a bridge. He sustained a stab wound on his chest. His face wrapped in packaging tape. He died of strangulation.

Beside him was a cardboard sign that read: “Pusher. Wag tularan. (Pusher. Do not imitate.)”

His mother, *Aling Norma started to break down even before we began the interview. It was the last day of her son’s wake before his cremation.

“Walang hustisya ang ginawa nila sa anak ko! Ang tinitira lang nila iyong maliliit, bakit hindi iyong ugat ang hugutin nila? (There’s no justice to what they did to my son. They only persecute the small [people], why don’t they uproot the source of all this?)” she cried in anger.

She paused for a while, and then scrambled for more words to say as she wiped her tears. But apparently, she could not.

Aling Norma’s daughter-in-law *Dina sat behind her. She was initially afraid to speak. She didn’t want her photos taken. She fears for their security.

Then surprisingly she began to talk, but still with a bit of restraint, narrating the night she last saw her husband and the days of searching afterward.

Dina said Jay would accompany her to work every night to keep her safe, not knowing that particular night was the last time she would see him alive, before he went missing the next day.

She searched everywhere, posted and distributed photos of Jay, and approached the police as well. No hope was in sight for nearly two days, until she heard a knock on her door.

The man said her husband had been found dead on the bridge several meters away from their house.

According to her, there were witnesses who saw Jay being forced to hop on a motorcycle. Two motorcycles carried two men each on board. They were masked and in civilian clothes, she said, recalling the account of witnesses.

One of the residents gathered around us during the interview came near us and was quick to share what he also heard. He said someone saw Jay and another man being taken out of a police precinct at dawn, both apparently dead. It turned out they were found dead, separately, on the same day. But the witness is afraid to speak, the resident said.

Meanwhile, sitting quietly at the wake was Jay’s relative, *Elias, who initially seemed to doubt our presence and purpose for the interview. He asked with a stern voice if we were part of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

After a bit of explanation of our work, he firmly whispered to my Swedish colleague, “Duterte is a killer!” before leaving the wake, clearly hurting and angered.

During a follow-up phone call, Jay’s father *Mang Boy revealed that there is no further police investigation into his son’s death. Although there was a Scene of the Crime Operatives (SOCO) team as Dina mentioned, he said they have not heard from the police yet since then. This, in fact, puzzles their family, he added.

‘Not quite accurate’

Like Aling Norma, human rights advocate Rosemarie Trajano thinks the victims of the killings and the current anti-drug campaign are “mostly coming from the poor people.”

Reacting to the general sentiment that the current government only or mostly targets low-level drug pushers and addicts in its anti-drug campaign, presidential spokesperson Ernesto Abella called it “not quite accurate” during a phone interview.

He mentioned that the government has recently named and gone after drug lords and peddlers in all sectors of society. Problem is, some drug lords are not in the country and the drugs are also manufactured elsewhere, he pointed out.

But Trajano, who is the secretary general of Philippine Alliance of Human Rights Advocates and convenor of In Defense of Human Rights and Dignity Movement (iDEFEND), noted of the innocent victims of the campaign in a phone interview. “In fact our children’s group mentioned that 9% of those killed were children and we do not believe that they are also drug users.”

In previous news reports of other media outlets, President Duterte said that innocent victims are “collateral damage” in his campaign against drugs.

[Story continues below.]

Tokhang and Double Barrel Operations on the first week of December. Photo by Lorela Sandoval

EJKs

But internal purges and extrajudicial killings (EJKs) cannot be denied, at least according to a few officials.

“Information came as early as June that those who are suspected to be involved in different drug syndicates are trying to eliminate already their assets at the bottom so they will not be able to point who are the uplines in their network,” PSSupt. Dionardo B. Carlos, Philippine National Police (PNP) spokesperson and acting chief of its Public Information Office (PIO), said in an exclusive interview.

He identified possible perpetrators such as gun-hires and erring policemen.

He said there are only two confirmed cases of EJKs of the 1,900 cases being investigated. He cited the two confirmed cases are considered premeditated or murder cases, which are now subjected to criminal cases. Only 22 of all these cases, meanwhile, have probable cause to conduct investigation.

“But 1,200 plus cases were dropped and closed, meaning, they did not see any irregularity during the conduct of operation, which only shows that they were just performing their duties,” Carlos said.

Meanwhile, a local barangay official in Manila, who asked for anonymity, confessed that when a person on their watch list ignores their warnings and continues to become a nuisance to their community, they let the police take matters into their hands – and that’s where EJK sometimes happen.

Senior deputy state prosecutor Richard Anthony D. Fadullon of the Department of Justice also believes there is EJK. “I don’t care about what’s reported in the news but I know that there are extrajudicial killings.”

Asked to put into proper context what EJK is in a follow-up email, he said it is “a misnomer” for him. “All forms of killings, not sanctioned by the law, are extrajudicial. Thus, homicides and murders are considered extrajudicial killings regardless of who the perpetrators are.”

Judicial killings, on the other hand, are “those sanctioned by the law.” For instance, he said, “If the death penalty in our country is restored, the imposition of such penalty and its subsequent enforcement would be in the form of a judicial killing.”

He said there’s no such thing as crime of EJK in Philippine legal statutes, just plain murder and homicide, so the “more appropriate term would be extra-legal killings. The term extrajudicial killing gained recognition/notoriety around 2007 when then UN rapporteur Philip Alston came up with his report stating that killings of journalists/media men and women/persons with varied political persuasions were perpetrated by state agents.”

What about rubouts—are these considered EJKs? “Rub-outs if proven to be such, would be considered extra-legal killings because it is carried out in contravention of the law and because the State does not have a policy allowing it to be done,” he said.

He also said that EJKs couldn’t be attributed to the police entirely “without the appropriate investigation first being conducted as there is no state policy to conduct extrajudicial killings.”

“The simplest way for media is to blame the police, but we must remember that there are many different people involved,” he added. “Let us not forget the drug lords and their organization that are just to eager to blame the police.”

Noted security consultant and SecurityMatters magazine’ editor-in-chief, Ace Esmeralda, also has this to say: “Uniformed policemen may pick up their on ‘police assets’ or ‘retained goons’ in the guise of police operations.

“Since there are so many policemen in the drug syndicates,” Esmeralda said, “it is no surprise that suddenly, in less than two weeks of the Duterte administration, the policemen are arresting left and right, day and night, several suspects with most of them ending up dead.”

—–

The next question to wrestle with now is: has the situation nowadays become worse than the darkest days of the Martial Law years? This post is an excerpt of a more extensive exploration of this topic. Catch it in the first issue of the newly revamped SecurityMatters Magazine, which will hit newsstands and bookstores in early 2017.

(Ed’s Note: Real names of the victim, his family, and other details in the account of the family, were withheld for security reasons as per request. This was part of a weeklong coverage with a Swedish daily.)